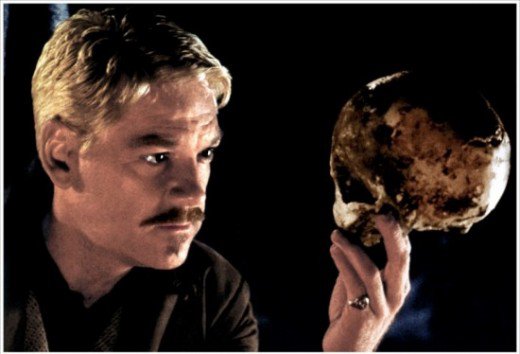

Climate change and its effects are pressing issues in our world today, but what about during the Renaissance? What does climate change have to do with Shakespeare’s Hamlet? While we might all be familiar with the Danish prince’s melancholy and philosophical quandaries, Philip Collington and Emma Collington say we should also examine how the play’s setting of Denmark’s icy coast contributes to Hamlet’s mental deterioration. In their Buffalo Humanities Festival talk, Philip Collington and Emma Collington use Hamlet to address the impact of the “little ice age” on individuals in the Renaissance.

Climate change and its effects are pressing issues in our world today, but what about during the Renaissance? What does climate change have to do with Shakespeare’s Hamlet? While we might all be familiar with the Danish prince’s melancholy and philosophical quandaries, Philip Collington and Emma Collington say we should also examine how the play’s setting of Denmark’s icy coast contributes to Hamlet’s mental deterioration. In their Buffalo Humanities Festival talk, Philip Collington and Emma Collington use Hamlet to address the impact of the “little ice age” on individuals in the Renaissance.

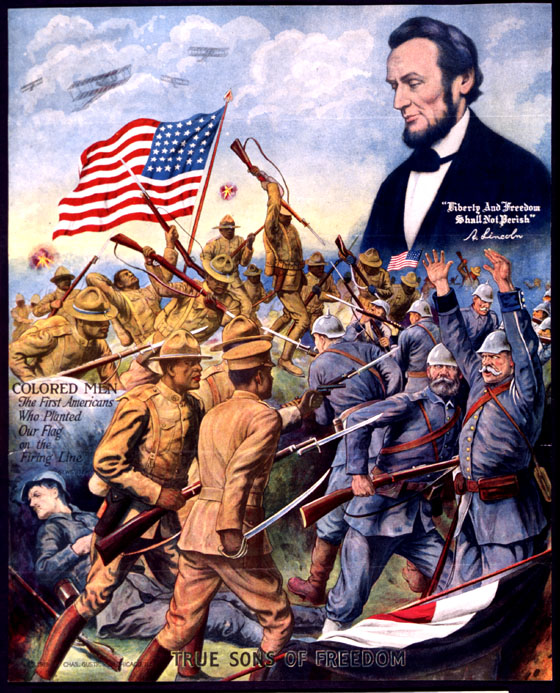

Roughly between the early 14th century through the mid-19th century, our planet experienced what geologists call the Little Ice Age (LIA), in which mean annual temperatures across the Northern Hemisphere fell due to the expansion of mountain glaciers across earth. While the time period of the Little Ice Age is contested, it did occur after what is known as the Medieval Warming Period and before our current period of warming that began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The LIA had significant effects on civilizations across the globe. In Europe, glaciers from the Alps expanded and “advanced far below their previous (and present) limits, obliterating farms, churches, and villages in Switzerland, France, and elsewhere.” All over the world, cold winters and wet summers ruined crops and harvests.

So how does Hamlet’s sensitivity to light, darkness, and cold reflect both Renaissance and modern theories about climate and mental health? To find out, you’ll have to join us on September 24 from 11:00am-12:00pm in Ketchum Hall, Room 113.

Philip Collington (PhD, University of Toronto) teaches Shakespeare and British literature at Niagara University. He recently published an article on Hamlet in Texas Studies in Literature and Language. Emma Collington studies psychology and biomedical sciences at the University of Waterloo, investigating the relationship between embryology and metastasis. She also volunteers as a peer mental health counselor.

Richard A. Bailey’s talk at Buffalo Humanities Festival will focus on contemporary American author Wendell Berry, a true renaissance man as seen in the wide range of topics covered in his writing. For Bailey, Berry serves as a modern-day prophet, whose calls for repentance are lamentations we should consider seriously, especially in communities, such as Buffalo, intent on “reviving.”

Richard A. Bailey’s talk at Buffalo Humanities Festival will focus on contemporary American author Wendell Berry, a true renaissance man as seen in the wide range of topics covered in his writing. For Bailey, Berry serves as a modern-day prophet, whose calls for repentance are lamentations we should consider seriously, especially in communities, such as Buffalo, intent on “reviving.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.